← Home

AI x Design Lab Research

2023-2025

-> Inclusive Design

-> Artificial Intelligence

-> Health Tech

-> Inclusive Design

-> Artificial Intelligence

-> Health Tech

Use of Artificial Intelligence to improve physical well-being.

This project looks at how AI can be leveraged to design inclusive digital health interventions that address lifestyle-related back pain. I used qualitative research methods, including interviews, observations, and workshops to uncover insights which directly informed design intent.

Research Overview

Back pain can happen regardless of age or ability. As we continue to adopt new ways of working (home, remote and hybrid), this presents challenges for workers to manage their back health. In the UK, the British Chiropractic Society states that 49% of people in the UK experience back or neck pain on a weekly basis, with 20% pointing to work as a key trigger.

This research aims to develop a personalised health intervention rather than general advice for backs through inclusive design research and application of AI. Read more about the research methodologies and insight in this paper (page 64).

This research aims to develop a personalised health intervention rather than general advice for backs through inclusive design research and application of AI. Read more about the research methodologies and insight in this paper (page 64).

1. Observations

Our observations research themes:

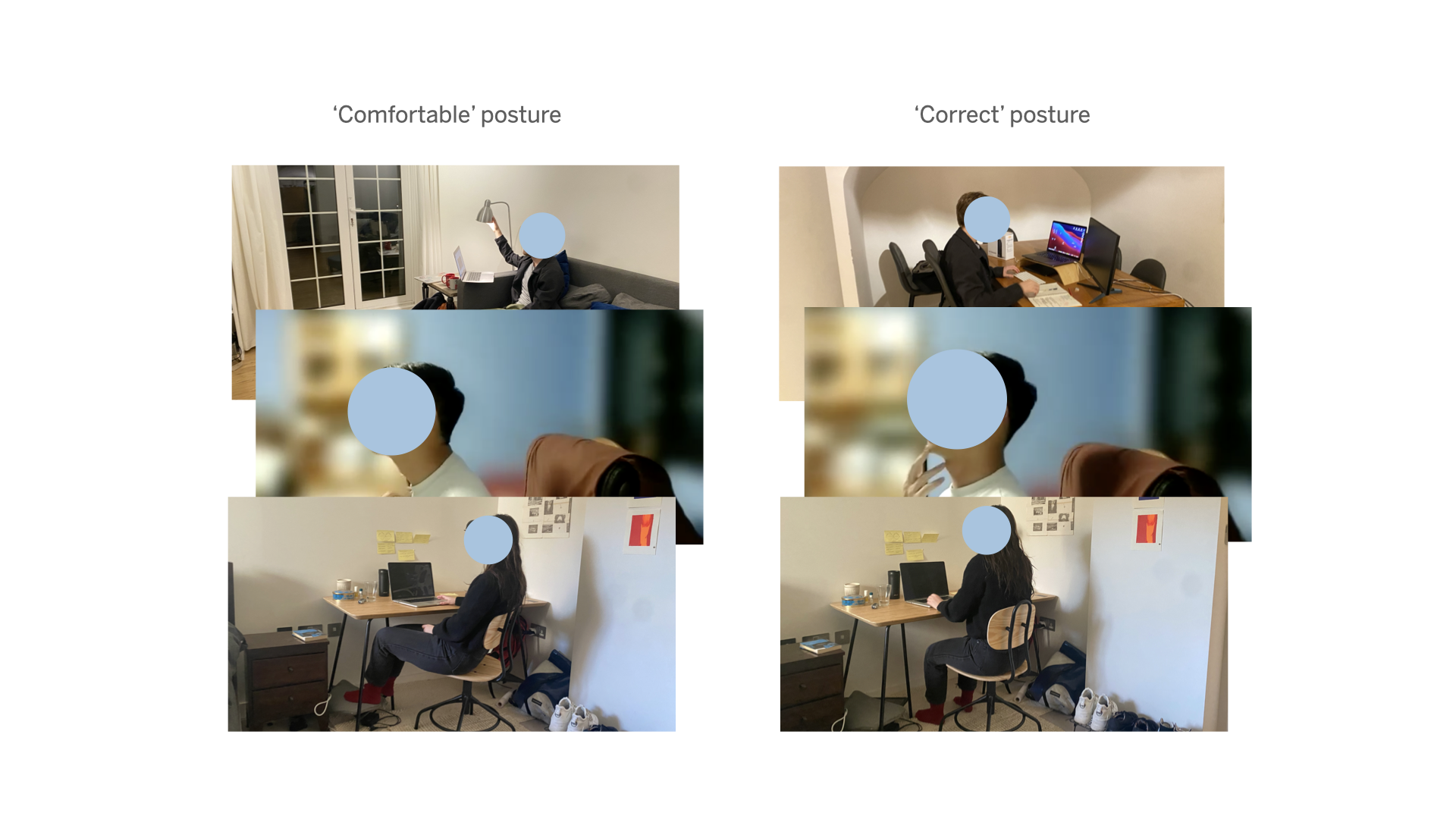

(1) Photo diary

We collected images of where participants worked, how they sat in different environments, and how their posture shifted across contexts — home, office, commute. This gave us unfiltered insight into real-world behaviour rather than self-reported habits.

We collected images of where participants worked, how they sat in different environments, and how their posture shifted across contexts — home, office, commute. This gave us unfiltered insight into real-world behaviour rather than self-reported habits.

(2) Prompts

Where possible, we promtped our participants to demonstrate

The observations surfaced both conscious decisions and subconscious habits that participants hadn’t articulated themselves.

- How they sit in different contexts

- What they think is a correct posture

- What they find comfortable

- What they consider ‘incorrect’

The observations surfaced both conscious decisions and subconscious habits that participants hadn’t articulated themselves.

Examples of collected photos︎︎︎

2. Interviews

Expanding on our themes, we identified key stakeholders to conduct interviews with:

(1) Expert interveiws

To better understand lifestyle-related back pain, we conducted semi-structured interviews with a range of specialists.

We spoke with chiropractors, back specialists, ergonomists, workplace wellbeing advisors, yoga instructors, and fitness professionals. Bringing these perspectives together helped us see the issue beyond posture alone, and understand how habits, environments, and daily work routines all contribute to experiences of back pain.

(2) User interviews

To structure the conversations, we created a mapping tool that helped participants trace their back pain journey: when it began, what was happening in their lives at the time, and what remedies they tried etc. Mapping these lived timelines grounded our design decisions in real experience rather than assumption.

Examples of quotes from interviews with Experts︎︎︎

Examples of mapping tool︎︎︎

3. Workshops

We facilitated a co-design workshop exploring how AI could be personalised and meaningfully integrated into the product experience.

The session brought together an interdisciplinary group - data scientists, fashion designers, textile researchers, and software developers. We were hoping to create an environment where technical feasibility, material knowledge and user experience all thinking in the same room.

This cross-disciplinary dialogue aligned constraints, and opened up opportunities.

Workshop at DesForm Conference, Hong Kong︎︎︎

Research Insight -> Design Intent

(1) Insight synthesis

We captured qualitative data via note-taking, conversational tools, audio-visual recordings, and photographs, before thematic analysis. The themes identified the aspects that we considered important to the context of lifestyle-related back pain.

(2) Design intent

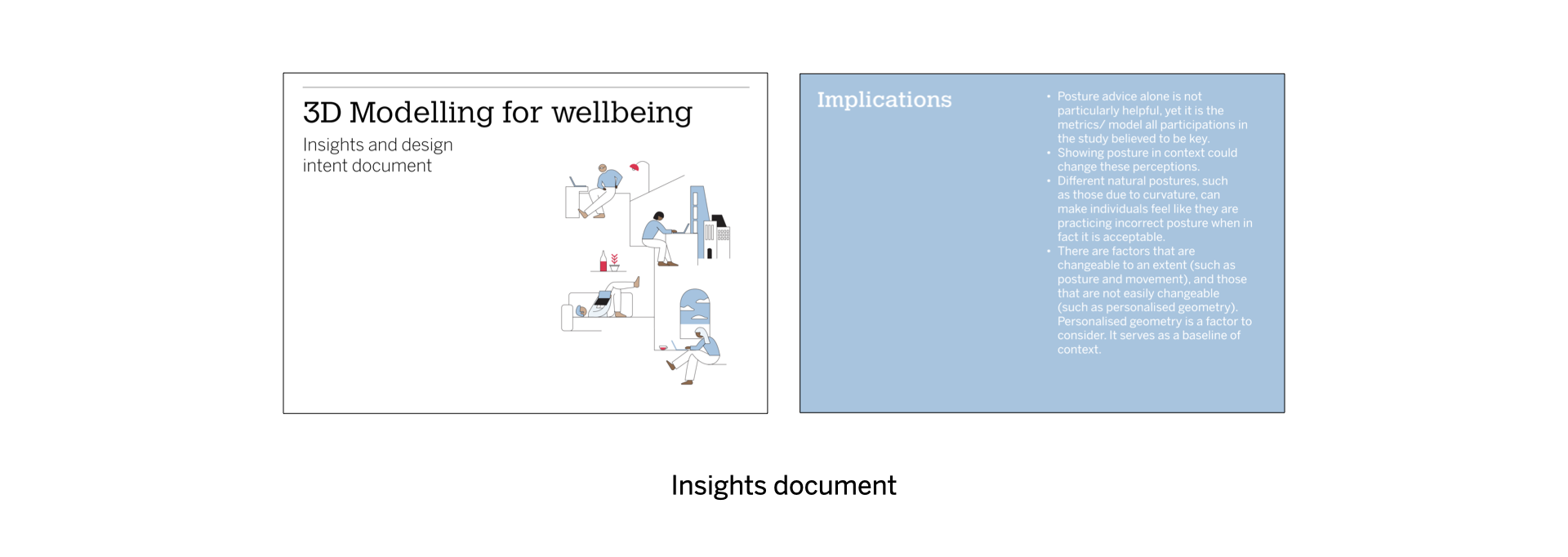

To translate research insights into design intent, we consolidated all the findings into a document ‘Insights document’, where we defined -

(3) Design outcomes

The qualitative research led to a web app concept, informed future research, and led to the final proof-of-concept prototype. View the research tool developments: Conversational Data Collection Tool or Qualitative Data Collection Tool, or the design outcome: AI for Wellbeing.

We captured qualitative data via note-taking, conversational tools, audio-visual recordings, and photographs, before thematic analysis. The themes identified the aspects that we considered important to the context of lifestyle-related back pain.

(2) Design intent

To translate research insights into design intent, we consolidated all the findings into a document ‘Insights document’, where we defined -

- Who is the intervention for

- What is AI’s unique role in this intervention

- Do’s and Don’ts

- Our definitions of an inclusive intervention

(3) Design outcomes

The qualitative research led to a web app concept, informed future research, and led to the final proof-of-concept prototype. View the research tool developments: Conversational Data Collection Tool or Qualitative Data Collection Tool, or the design outcome: AI for Wellbeing.

Example of Insights document detailing research insights and design intent︎︎︎

Research insight translated to Design intent︎︎︎

Many participants believe there is a single ‘good posture’ - usualy upright and straight. Our research with revealed that back pain at work is not only related to the straightness of the spine. Pain is influenced by movement level psychological stress, workload, and environment. Because the causes are multidimentional, the intervention couldn’t focus on posture alone. It needed to process multiple inputs at once and respond dynamically.

Design intent : The intervention should be able to interpret multidimentional data. The markers that are relevant to work include movement, environment, posture, stress.

Insight 2 : Inclusion requires personalisation

Some people have spines that are more skewed or curved than others - we learnt from experts that this is all perfectly natural. When it comes to giving posture advice, one size doesn’t fit all. We cannot rely on a single benchmark of “correct” posture.

Design intent : The intervention needs to respond in real time, adapting to individual bodies and work habits to establish a personal baseline - rather than enforcing a universal standard.

(3) Any effective design intervention will have to be contextual.

The workplace/ work set up varies. Some participants worked at ergonomic desks, others from sofas, on the train etc. This means that advice that ignores context quickly becomes irrelevant.

Design intent 3: The intervention needs to be context-aware, rather than assuming a fixed workspace. This will enable relevant and actionable behaviour change.

(4) Tagiblising the causes of back pain helps to make its management more actionable.

The contributors of back pain are multifaceted, the research revealed the limitation of considering static posture as the sole contributor to the narrative of back pain. The research also highlights the benefit of understanding what these factors affect back pain for people to enact change.